universal stories: the photography of Rania Matar

I made a wonderful discovery while visiting the MFA’s thought-provoking exhibit, She Who Tells a Story: Lebanese-American photographer Rania Matar lives a short walk away from me here in Brookline.

As an art-loving blogger, I had to meet this woman!

Over coffee at Koo-Koo Cafe, Matar and I discussed the simultaneous exhibits of her work at the Museum of Fine Arts and Carroll and Sons Gallery. Selected pieces from Matar’s A Girl and Her Room are at the MFA, while Carroll and Sons features highlights from her latest body of work, L’Enfant Femme (“child-woman”).

L’enfant femme is a French expression. Like all idiomatic expressions, it’s a bit hard to translate exactly into another language, but as Matar explained to me, it conveys a young girl’s self-confidence, her awareness of her femininity; of being a little woman.

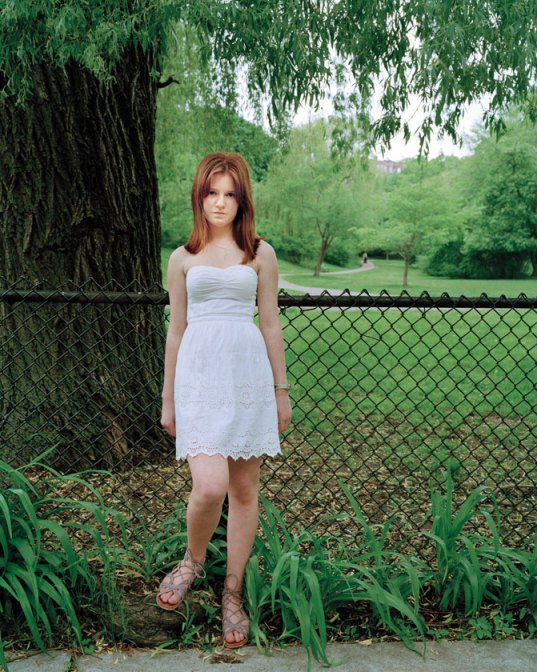

Do you remember how utterly awkward you often felt, or were made to feel, as an adolescent? Matar’s photos capture those universal feelings of otherness, of self-imposed and societal isolation. But they also show when girls feel strong and self-confident enough to be little women, comfortable with themselves and who they’re becoming.

As someone who knows what it’s like to live in the Middle East and the West, Matar tries to capture “the universality of humanity” in her photographs. But Matar’s photos are particularly fascinating, because they also poke holes in Western preconceptions of Middle Eastern culture. Not only that: her pictures are a bridge viewers can traverse to explore what it means to be female in the 21st century.

At their extremes, both Western and Middle Eastern societies portray two drastically different female stereotypes: hyper-sexualized, overexposed, twerked-up/perked-up women, versus veiled and hidden women, isolated, segregated and nonexistent to the outside world.

Where do we, as girls and as women, fit between these two extremes, and how does this middle ground look and feel?

How “modern” are our liberal Western values if we won’t let women make their own choices about what they want to wear? Can veiled women be feminists? Some women say that it’s liberating to wear the face-covering niqab: you’re free to glide around, away from the prying eyes of others, and there are no bad hair days.

Have you tried to strike up a conversation with a woman wearing a niqab? It can be daunting, even for someone as gregarious as me. You may say it’s your choice to cover yourself completely, but I would argue societal norms influence what you’re wearing: the same goes for us in the West.

She wore a headscarf, too. Madonna and child, Don Lorenzo Monaco, Florence c. 1410 (Wikipedia)

When you get dressed, you’re picking your fashion weapon of choice: headscarf or bikini? Miniskirt or chador? Is one any more liberating or expressive than the other? It’s all in the attitude, as Matar’s photos show us…

Matar began her career as an architect. Her training shows in the staging and design of her photos; in their precision, strength, and symmetry. Nothing in her images feels superfluous. She began to pursue photography full-time after taking pictures of her four children. Matar now strives to capture that same level of intimacy with all of her subjects.

After September 11th, Matar turned her focus to the Middle East. The news was so upsetting to her that she became protective of that area of the world, and wanted to show a side of Middle Eastern culture that wasn’t portrayed in Western media.

I became aware of being in the U.S. as an Arabic woman, as a Middle Eastern woman…The ‘shock and awe’ that we saw in America during the Iraq War felt so abstract…

…Things like [war and 9/11] make you become who you are. They give you more awareness of who you are. I have two identities, and I can be both. It made me realize that people are the same no matter where you are, so I decided to photograph that…

…In 2006 I went to Lebanon to visit with my kids. The bombing started between Israel and Hezbollah, and it was very traumatizing. All the memories of growing up in Beirut during the war came back to me. But I’m not a war photographer, and I felt very scared for my kids–we got stuck there.

My father-in-law arranged for us to leave [Lebanon and] take cabs to Damascus. There was this truck filled with women and kids–I was so wrapped up, taking their photos. Every single one of those people had a story. After the war, after the bombing, the media goes away. But that’s when war becomes real to the people who remain there.”

Even from behind a veil, we mothers want the same things for our children. We want to feel hopeful about their future, even when we worry about the present.

“I love working with people,” Matar says. “I treat them with respect. I try to build relationships with them through my photographing them. Landscapes aren’t my thing. I prefer people in all their messiness and complexity.”

For A Girl and Her Room, Matar collaborated closely with her teenage subjects. She remembers: “I was the exact same way 30 years ago in Lebanon as the girls I photographed.” She focused on the similarities between the American and Middle Eastern girls, not the differences. “Maybe one is wearing the hijab, [but] at the core they are the same.”

Matar prefers medium- and large-format photography to digital, saying its slower style is more fitting to the craft of photography. But she made an exception for the Girl and Her Room series, which is digital. She collaborated closely with the girls, getting input from them on how they wanted to pose and what they wanted in the background. The immediacy of the digital format also let Matar and her subjects see and discuss the results of their work together during the shoot.

But Matar went back to film, using a medium-format camera with the younger girls for L’Enfant Femme, explaining that:

[Film is] more expensive [than digital], but I love the grain of the images and the tone. Images look and feel different in print. With print photography, the whole process of my work is different…I like to move around when I shoot. The camera takes the girls out of their comfort zone, because it’s not digital. They pose differently than they do for Facebook and other social media; they don’t see [the photos] until after they’re developed.”

For L’Enfant Femme at Carroll and Sons, photos of girls with similar poses hang across from one another, reflecting each other. Stripping away the external cultural cues, the universality of the facial expressions and body language Matar reveals makes it hard to tell who’s from Beirut and who’s from Brookline…

Matar is now working on Women Coming of Age, portraits of middle-aged American and Middle Eastern women. She’s also begun a new project about boys. To see more of Rania Matar’s photography, visit www.raniamatar.com.

Matar’s care and relationship-building with the women (young and middle aged) is evident in the stunning results. Thank you for your thoughtful presentation of her work.

Thank you, Andrew! I agree. It’s quite a talent to be able to wade into unfamiliar territory and take such intimate and respectful photographs.

Brilliant blog, great to see so many photos. So glad I was able to see the MFA show with you.

xx dottie

Hi Dottie! Thank you — same here. So many artists, so little time! Amy Sillman at the ICA is next…

wow – as a lebanese american i am in awe for so many reasons. bravo, Matar. stunning photos. moving. powerful. love love love!

Thank you so much! I’m really fascinated at how women are portrayed in both western and eastern cultures, and Rania’s photos explore this and many other issues. Do try to see the MFA exhibit if you can, the other artists are as equally intriguing.

nice post, jen. she’s the best, isn’t she?!

Thank you, Toni! She really is 🙂

and PS…I meant to add: I LOVE the photos she took of you 🙂 xoxo

Lovely, sensitive and haunting images. A most thoughtful and sensitive article. Thanks for introducing me to Rania Matar.

thank you, Marie! I’m so glad I got to meet Rania in person and get her perspective on her photographs, her techniques and creative process. Her work really resonates with me. The MFA show “She Who Tells a Story” is really interesting, too. I’m glad the museum is featuring more women artists from other parts of the world. Good to see, and hope it’s a trend that continues. Anyway, thanks for reading, and for commenting!

Thank you, Jen, for writing such an inspiring and amazing story about Rania Matar. I truly enjoyed her exhibit at the MFA as well. The comparison and knowing that we are all so similar no matter where we live in the world is so brilliantly portrayed in her photographs.

Much love, Joanie

hi Joanie, thanks for reading my blog, and for commenting. Yes, she is an inspiring and amazing woman, and I loved seeing her photos with you at the MFA! much love back, Jen xxx

totally can relate to her work. as a young girl growing up in the states but in a middle eastern home, it was very confusing and the teenage years were very difficult to navigate here!

hi Suz – I knew you’d totally relate to Rania’s photos. One of these days I’ll get the two of you in a room – she should take your picture, actually, for her series on women! xoxo

This is one of the best write-up on Rania Matar that I have read – excellent work@

Rania is a first class photographer who manages to shoot from the heart while maintaining a strong hold on the technical. .

why thank you, Ian! And thank you for subscribing 🙂 I will be sure to pass along your kind words to Rania.